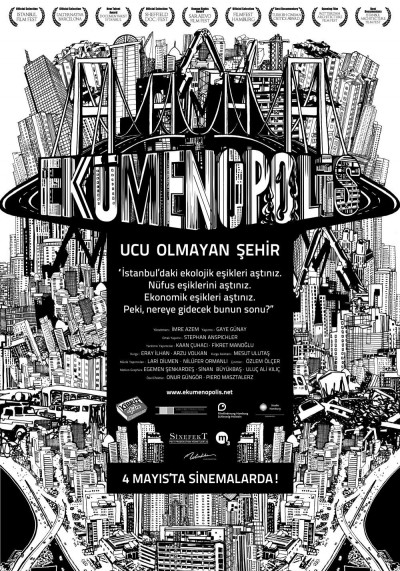

Sunday October 12th 2014, Ekümenopolis – city without limits. Directed by Imre Azem 2011, 93 minutes, in Turkish with English subtitles. Door opens at 8pm, film begins at 9pm.

Eukemonopolis is documentation about neo liberal city development in Istanbul and the aspiration of its political leaders of turning it into a global city, one of those cities like London, Tokyo, Amsterdam or São Paulo, that shape globalisation and form the network of global cities where the service, banking and real estate businesses accumulate, where mega events takes place and a hegemonial hipster culture is cultivated. While the global alpha, beta and gamma cities posses the intellectual knowledge, tools and power the global division of labour is further extended, with the majority of factory production being outsourced to those parts of the world where people earn a shit for their 60 hours working week, have no labour rights whatsoever and endanger their health and well being by working in super precarious conditions, let alone the environmental destruction that this system of global division of labour provokes. Eukomonopolis shows quite in detail what the negative effects of repressive neo liberal urban development in Istanbul mean to local citizens and to the city’s natural environment while it also explains concepts like the global city (which was developed by Saskia Sassen) so that we can look at our own living environment and have more tools at hand to better understand what happens around us and affects us. We can develop strategies and actions to be solidare with the exploited people worldwide and get active locally in order to develop and realise our own strategies in contrast to that what is opposed on us by the state and its institutions, urban planners and the capitalistic system.

As further background we want to provide a text about urban development in the city which is part of more a comprehensive report about squatting in the Istanbul and a collection of reports about radical grassroots neighborhood and factory organisation provided by the the solidarity campaign for left neighborhoods in Istanbul, translated from german to english. Even though the documentary does not relate those particular stories, those texts may shed some light on local resistance against the urban development that takes place in the city.

Reclaim the Urban Commons

from Reclaim the Urban Commons: Istanbul’s First Squat

Turning Istanbul into a ‘global hub’ has been a central issue in Erdoğan’s election campaign and the administration of his Justice and Development Party (AKP). His understanding of a city, meanwhile, appears to be that of a resource which can be drained for the highest possible profit. In recent years, Istanbul has seen a series of violent urban transformations for which the term ‘gentrification’ is a plain euphemism. Entire low-income neighborhoods and shanty towns (gecekondu) have been demolished and sold to large-scale investors.

In order to do so, the government has systematically established the necessary institutions: a law about earthquake security provides the judicial basis to declare houses unsafe for living and up for demolishing. The public housing administration TOKI has the sufficiently wide ranging authority to execute this process.

One of the most prominent examples has been the neighborhood of Sulukule, one of the oldest permanent Roma settlements. 3,400 people were manipulated or threatened into selling their homes to private investors, or eventually forcefully evicted. As an ‘alternative’, they were offered apartments in large TOKI-build complexes far away from both the city center and their original work places and schools.

Not only were activist networks interrupted, jobs lost and big families herded together in very small spaces — creating an additional psychological burden — the rents for the TOKI-apartments were often too high for the evicted to afford them, practically leaving whole families in the street. Most of the former inhabitants of Sulukule have tried to move back to the vicinity of their old neighborhood. The houses they once owned there were demolished in 2010 and have since then been replaced by houses and offices almost ten times the price.

A similar fate has hit other neighborhoods, like Ayazma and Tarlabaşı. In the latter, a very central but run-down neighborhood right next to Taksim Square and Istanbul’s main shopping and party area, the process has already started. A large advertisement banner displaying the area’s sterile and prosperous future is pinned on the decayed facades of Tarlabasi Boulevard, making the contradictions of the rapid and violent transformation process all too obvious.

This government-directed ‘urban renewal’ does not stop at the demolition of low-income neighborhoods. Turkey’s Prime Minister seems to have quite a vivid imagination when it comes to his self-declared ‘crazy projects’. Among them are a third bridge over the Bosporus, connected to a six-lane highway in the north of the city, which, in turn, is supposed to be connected to a third airport. These projects will have a dramatic impact on Istanbul’s environment.

The first two Bosporus-bridges already caused the city to rapidly expand northwards, overrunning forest areas and contaminating lakes in its way. Istanbul is currently supplying itself with drinking water from Kocaeli, another city located about one hundred kilometers away, because the fresh water reserves around the metropolis have already become insufficient.

The original strategic plan for Istanbul, developed in 2009, foresaw a way to direct urban sprawl by means of transportation-incentives in a way that would protect the forest regions between Istanbul and the black sea. Erdoğan’s government simply cancelled the plan. Using the traffic congestions as a pretext, the clear aim behind the third bridge, the highway and the new airport is to encourage the emergence of new commercial centers, regardless of their long-term effects on Istanbul’s environment and inhabitants.

Probably one of the craziest among the crazy projects is the creation of a ‘Kanal Istanbul’, which was announced in 2011. The Kanal Istanbul is intended to parallel the Bosporus, to form another thoroughfare between the Black Sea and the Marmara Sea. Along with the channel, Erdoğan intends to build form scratch two new satellite towns with a capacity of about 4 million people, exceeding the population of most of Europe’s capital cities.

As Yaşar A. Adanali, PhD candidate at the Department of International Urbanism at Stuttgart University writes with regard to these ‘crazy projects’, neither the public, nor local authorities were ever part of the decision-making process. He uses the term “state of emergency regime of planning” to describe Erdoğan’s way of placing urban planning outside the reach of democratic checks and balances or public intervention.

Who benefits from the violent urban transformations is easy to deduce: Istanbul ranks fifth on the list of the world’s cities with the highest number of billionaires, while at the same time Turkey is ranked last of the 31 OECD countries in terms of social justice. People involved in real estate and the construction business pose the majority among the country’s 100 richest persons. While low-income families, Roma people, and — as in the case of Tarlabaşı — Kurds and transgender communities are forcefully removed from the center, the profit of most large-scale construction projects goes directly to the very top of the income scale.

Squatting in Istanbul is thus a statement for social justice. But it also means reclaiming the ‘right to the city’, evoked by scholars like Henri Lefevbre or David Harvey. To say “now this is ours, this is everybody’s!”, like Selin and her friends did in Yeldeğirmeni is to resist the extremely authoritarian ways of commercializing the urban commons. It is a claim to urban democracy. This kind of resistance reached an unprecedented momentum with the occupation of Gezi Park this summer. After all, everything started out as a protest against yet another large-scale urban renewal project, intended to replace the last park in Istanbul’s city center with a shopping mall.

Resistance in the hood

from the solidarity campaign for left neighborhoods in Istanbul

Istanbul, the capital of gentrification. Here you are kicked out of your home faster then in Kreuzberg if you do not earn enough money, if you are Kurd or Roma, or if someone from AKP rather wants to see a hotel where you erected your hut. But In some neighborhoods this is different. There, militant revolutionary groups have a say, and there are not only a few of them.

In Kücük Armutlu, Gazi Mahallesi, Okmeydani and other neighborhoods the state has no power anymore. Those areas have been built up by the radical left itself and earlier as the Gecekondus, the self-constructed houses. There the inhabitants are backing the revolutionaries. You live together and trust each other. The state and its institutions are not needed here and nobody wants them. The state encounters resistance when it tries to invade the areas with armored vehicles, the so called “Akreps”, with special police units and water canons. Resistance is not squeamish. Stone, slingshots and Molotov cocktails are the means of every youth. The militant core is sometimes taking Kalaschnikow’s or shotguns in order to get rid of those unwanted visitors.

This resistance is the precondition for the social protests that are being formed. They are quite diverse and aim for better living quality in the poor neighborhoods. In Kücük Armutlu, a big community center is being self-constructed, and is going to include a Cemevi, an Alevist house of prayer, rooms for events and an own non-governmental school that will allow the local youth to gain education. Another project is tackling the energy supply of the neighborhood. Left architects and engineers are self-constructing wind turbines that shall be mounted on the roofs of the houses and even self-constructed solar systems are in the process of planning. A community garden shall enforce food security by breeding seeds that are then distributed among the local community for their own gardens.

Another big project is located in Gazi. Here, a building that has been squatted by revolutionaries is becoming a self-organized addiction clinic. The reason for this project is the advance of mafia and drug gangs that are supported by the state in order to contest the left neighborhoods by flooding the streets with drugs. This situation is not only opposed violently but also with a offer to addicts to get out of their addiction. Trained doctors and psychologists are working here voluntarily. During the therapy people can learn vocational skills in order to find their way back into society. The struggle against gangs and drugs may seem odd for the German left. In Turkey it is an important struggle as the state tries to crack down on the left in their neighborhoods by means of gangs often recruited from the right, just as the FBI that flooded the Black Panther neighborhoods back then with drugs. The activist Hasan Ferit Gedik died in September 2013 in the context of those conflicts. He got shot on the street by gang members during a demonstration. The clinic in Gazi is named after him.

All those projects are under thread. The poor neighborhoods are threaded by gentrification. The “urban transformation” as it is called by the ruling AKP party destroys long grown social and cultural milieus and forces the poor citizens into homelessness or to leave their neighborhoods. Drug gangs and police repression do the rest. Hundred’s of raids take place every year in the left neighborhoods, often with people being injured and arrested and sometimes with people being killed. If the Turkish state succeeds in repulsing the revolutionaries from their neighborhoods, these areas would soon look like the other gentrified hoods like Tarlabasi and Sulukule where a social culture developed over years has been driven out by neo-liberal urban restructuring. The old inhabitants got replaced, new buildings have been built that they cannot afford any longer.

We want to support the left in Turkey in their struggle to keep their important positions they have been fighting for and therefore we try to build up a long term solidarity campaign with the revolutionaries in Turkey.

Gecekondularda Direniş

from the solidarity campaign for left neighborhoods in Istanbul

Istanbul kentsel dönüşümün başkenti. Eğer paranız yoksa, Kürt veya çingene iseniz ve AKP yaşadiğinız alanda bir hotel veya AVM inşa etmek istiyorsa, Berlin Kreuzberg deki bi ev sahibinden daha hizli bir şekilde evinizden olabilirsiniz. Bazi mahallelerde ise bu durum farkli: Türkiye’de bulunan bir çok devrimci militan grup, inisiyatifi ele almiş durumda ve kendi çapında mahallesini korumaktadır.

Küçük Armutlu, Gazi Mahallesi, Okmeydanı ve bu tür mahallelerde devletin sözü geçmemektedir. Bu mahalleler daha önce gecekondu mahalleleri olarak isimlendirilmişti. Burada bulunan devrimci gruplar, mahalle sakinleri tarafından korunmaktadir. Mahallede herkes birbirini tanır. Böylesi yerleşim yerlerinde devlet veya devletin çeşitli kuruluşlari halk tarafindan kabul edilmemektedir. Devletin kolluk kuvvetleri Akrep, TOMA,vs. bu semtlere girmeye çalıştığında amansız bir direniş ile karşi kaşıya kalmaktadir. Bu direniş büyük bir miltan duruşla kendisini göstermektedir. Taş, Sapan ve Molotoflar buradaki direnişi sergileyen gençlerin kullandıkları “silahlardır”. Militan devrimci güçler, devletin olası bir saldırısı veya provakasyonu girişiminde kalaşnikof veya av tüfeklerini kullanmaktadir.

Bir direniş sivil projelerin gerçekleşmesi için kaçınılmaz bir yöntem haline gelmiştir. Sivil projeler çeşitli biçimlerde kendini gösterir ve hedefi ise böylesi yoksul mahallelerdeki yaşam koşullarini pozitif yönden etkilemektir. Örnek olarak: Küçük Armutluda halk menfaatleri için, kendi insiyatifi ile dernekler kurulmuş, cemevi açılmış ve etkinlikler düzenlenmiş. Bu proje çerçevesinde, ekonomik koşulları uygun olmayan çoçuklar için eğitim olanaklari da sağlaniyor. Başka bir proje ise mahallenin enerji sorununu gidermektir. Mimar ve mühendisler rüzgar türbinleri veya güneş enerjisi sistemleri inşa edip çatılara kuruyorlar. Gıda sorununu gidermek üzere halk bahçeleri kurulmaktadir. Bu halk bahçelerinde çeşitli tohumlar üretilip mahalle sakinlerine dagitilmaktadir.

Bir önemli başka proje ise Gazi Mahallesinde gerçekleştirilmektedir. Burada devrimcilerden işgal edilen bir bina, bağımlılık kliniği olarak kullanilmaktadir. Bu projenin hedefi ise, devlet tarafından desteklenen çetelerin yaydiği esrarın, devrimci mahallelerdeki halkı yozlaştirma ve bağimlılığa sürüklemek girişimine karşi mücadele etmektir. Doktor ve psikologlar bu projeye destek oluyorlar. Böylesi tedaviler ile amaç gençleri bağimliliktan kurtarıp yeniden topluma kazandırmaktır.

Bütün bu yoksul mahallelerdeki projeler ise devletin kentsel dönüşüm projeleri çerçevesinden dolayı tehlike altina giriyor. Kentsel dönüşümün bir başka sonucu ise senelerdir gelişen sosyal ve kültürel ilişkilerin yok edilmesi ve yoksul halkı evsizliğe sürüklemektir. Sene boyunca gerçekleştirilen polis baskınları sonucunda böylesi mahallelerde tutuklamalar, yarali insanlar ve ölümler gündemden çıkmamaktadir. Bu durumlarda, bizler sadece birer izleyici, takipçi olarak kalmak istemiyoruz. Bunun için türkiyeli devrimcilerle uzun vadeli bir dayanışma kampanyası başlatmak istiyoruz.

Bu tür projelerin amacı insanların birşeyler ögrenip kendi sonuçlarını cikarmayı sağlamaktır. Devletin ve sermayenin bizim burada gün geçtikçe daha zor koşullarda sürdürdüğümüz hayatlarımıza, yaşadiğimiz mahallelere müdahale etmesini zorlaştırmalıyız.

Factory without bosses

from the solidarity campaign for left neighborhoods in Istanbul

Self-organized production is beautiful and helps everybody. Kazova Tekstil in Istanbul shows how.

There is a nice clothing store just 20 minutes away from Taksim, in the neighborhood of Sisli. “Diren Kazova” is written above the shop windows, the floor is covered with big cobblestones, paintings and artfully collages are mounted on the walls. Male and female shirts are being sold, sweaters, pullovers and cardigans.

But Kazova Tekstil is not just another nice fashion shop, it distinguishes itself fundamentally from the other hundreds of thousands of perceived shops in the area. The shop is the result of months of labor conflicts inclusive strikes, demonstrations, occupations and tear gas. The story goes like this:

Kazova has been just a “normal” textile factory in Istanbul as Turkey is one of the major producers of textiles. Kazova produced for local companies and for western corporations, like Lacoste, Mango or Marco Polo. But this didn’t make it any better for the workers. The wages were crap, the supervisor answered complaints sometimes with a baseball bat, the working conditions were just horrible.

People got fired all the time and in January 2013 the owners decided to shut down the factory completely. The workers did want to prevent this. With support from lawyers of CHD a legal battle for the factory machines was initiated, claiming them in compensation for month of unpaid work. In order to raise pressure demonstrations has been organized, sometimes in the street of Istiklal, sometimes in front of the house of the boss. The factory has been occupied and needed to be guarded as the bosses composed themselves to take away the machines clandestinely what finally didn’t succeed.

In the course of that labor struggle a new inter-relation was formed with the movement emerging from the Gezi protests : “Gezi was very important for us”, explains one of the workers at Kazova that is member of the revolutionary grassroots union DIH (Devrimci Isci Hareketi). “Previously we only fought for punctual improvements in our factories. Even if you win everything will be again at stake a few month later and you get fired. Here we start to change the relationship with the production process itself.”

Kuzowa became a symbol of the movement. It is possible to produce without bosses, and it even works better: the wages are higher and prices of the products dropped. Who needs capitalists?

Film night at Joe’s Garage, warm and cozy cinema! Doors open at 8pm, film begins at 9pm, free entrance. You want to play a movie, let us know: joe [at] squat [dot] net