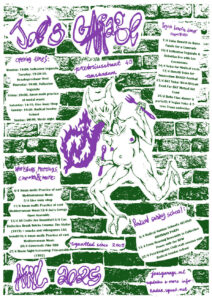

Zo./Su. 26 feb. 2012, 19:00, Filmavond, Carlos (Olivier Assayas, 2010, fr, 185′, english subtitles). Exceptionally, doors open at 19:00! Films starts at 19:15 pm. There will be soup and bread served during this long evening.

Terrorist? Revolutionary? Or just a cynic? This continent-hopping biopic of Carlos the Jackal suggests greed and ego won out over principle, writes Peter Bradshaw

Terrorist? Revolutionary? Or just a cynic? This continent-hopping biopic of Carlos the Jackal suggests greed and ego won out over principle, writes Peter Bradshaw

The Pimpernel of Marxist-Leninist terrorism is back. For years, Carlos was the spectre haunting Europe, known to western newspaper readers by one single photo: a plump, bespectacled and smugly smirking headshot reproduced with such Warholian persistence that it became an icon of menace. His fugitive invisibility made literary theorists of many, entertaining the feverish notion that he did not exist, that “Carlos” was effectively a socio-cultural construct, a bogeyman invented by the media-political complex to sell papers and to justify the erosion of civil liberties. Carlos’s eventual capture and imprisonment in the 1990s, revealing him to be abjectly human, was a real letdown, as if Osama Bin Laden had been arrested working in a Carphone Warehouse in Watford.

French film-maker Olivier Assayas has now released for the big screen a concatenation of his sweeping TV miniseries about Carlos, starring Édgar Ramírez as the Venezuelan-born revolutionary who abandoned university studies in Moscow in 1970 and travelled straight to Beirut to join the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. The film appears in two versions. The edited-highlights cut weighs in at a chunky two hours and 45 minutes. Or you can sit down to the whole thing: five-and-a-half hours, end to end. It is a measure of Assayas’s showmanship, flair and sheer narrative drive that this super-epic version is actually very watchable and more or less flies by. I’ve seen 80-minute films that felt longer.

As he affects the inevitable beret and cigar, Carlos looks a bit like the evil twin of Che Guevara, and in some ways Assayas’s movie is the evil twin of Steven Soderbergh’s two-part study, Che. Where Che appeared to be the romantic revolutionary leader, however, appearing at the head of a united force, Carlos seems an increasingly jaded terrorist, dedicated – in fine, Life-of-Brian style – to battling with, and undermining, the moderates of his own movement: a globe-trotting ideologue and sexual egotist. In Assayas’s film he appears not as a heroic force, but as the dismal mendicant of the Soviet Union, maintained in hideouts and weaponry by Moscow through its client state East Germany, and by Syria and Libya for whom it is convenient to retain the services of Carlos and his acolytes as a roving expeditionary force for mayhem. Finally the Berlin Wall comes down, taking Carlos’s career with it, and he appears a sleazy and seedy figure, washed up in Sudan where he improbably claims to be a Muslim, getting liposuction for his “love-handles” and apparently evincing not the smallest interest in the Palestinian people.

Assayas sees Carlos’s greatest moment as containing the seed of his downfall: his storming of the Opec convention in Vienna in 1975 during which he and his gang took hostages but failed to carry out the secret plan of killing some of them – most prominently Saudi Arabia’s Sheik Ahmed Yamani – a perceived failure of nerve that caused his expulsion from the PFLP. Here, Carlos popularised or even invented the aircraft hijack as the essential trope of 1970s terrorism: the theatrical gesture that doubles up as bargaining chip and getaway transportation. Carlos got a plane to fly to Algeria, whose government is shown to superintend the payment of $20m of ransom money from the Saudis for Yamani’s safety. A pro-Palestinian gesture turns into a mendacious blackmail spectacular, and at this moment Carlos becomes an intercontinental blowhard, whisking from safe-house to safe-house, existing in a network of untraceable money, and in a grey area between antisemitism and antizionism.

Little of the film is about Carlos’s super-inflated reputation in the media, though it might be interesting to make a movie about him in which he never appears on screen. Assayas simply flits alongside Carlos as he travels from Beirut to London, to Paris, to Damascus, to Tripoli, to Berlin, to Khartoum, angrily and tirelessly haranguing his comrades in various languages about their lack of courage, lack of obedience to his orders, and lack of tolerance about his need to have sex with other people. Ramírez’s performance as Carlos has fluency and swagger. There is little to show the inner man: although he has one bizarre monologue about his tender and sensual passion for weapons.

This is a film about the spectacle, or perhaps more specifically the secret spectacle, of a shadowy individual with a military flair for terrorism and a monkish vocation for revolution in its most rigidly abstract sense, which resulted in an existence that was not “stateless” exactly – Carlos’s privileges were granted by the super-state of Soviet communism – but nomadic, lonely, galvanised by the compulsive preparation for violent assault and the fear of arrest. And getting legal representation from Jacques Vergès (Nicolas Briançon) – the notoriously amoral fast-talker beloved of murderers and tyrants, and investigated in Barbet Schroeder’s documentary Terror’s Advocate – accelerates Carlos’s descent into cynicism.

Assayas’s Carlos is a television-drama-turned-movie that interestingly injects a boxset quality into its idea of epic. There are big establishing shots of each of the foreign cities where the latest episode occurs, but the drama itself, despite its multinational setting, is all intimate, domestic, steamy, almost soapy. It really does rattle along, and Ramírez is a very convincing Carlos: on the run like a bank robber, an ideologue with no ideas, left marooned when the tides of history turn against him.

Film night at Joe’s Garage, nice, warm and cozy cinema! Doors will exceptionally open at 19:00, film starts at 19:15, free entrance. You want to play a movie, let us know: joe [at] squat [dot] net